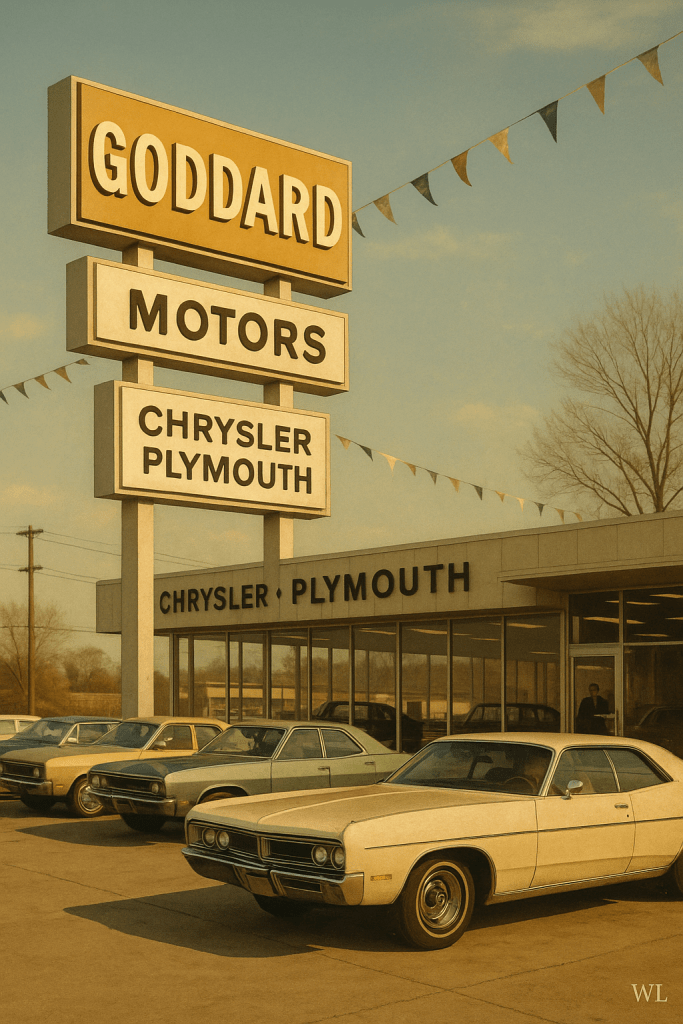

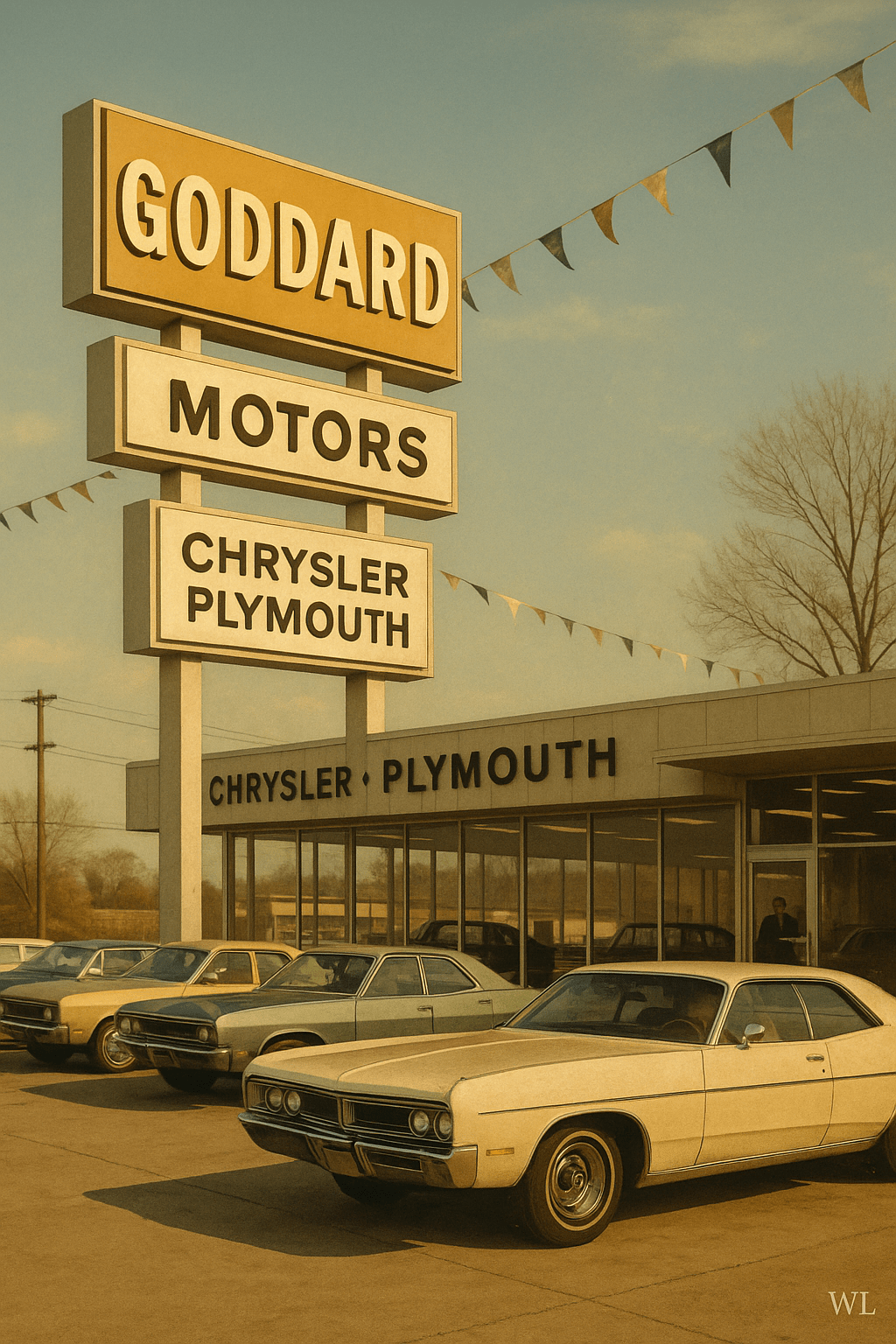

When I was a kid growing up in St. Louis County, few places held more magic for me than Goddard Motors, the Chrysler-Plymouth dealership where my dad worked. It sat just south of the old Northland Shopping Center on West Florissant Road, that bustling landmark of the late 1960s and early ’70s, when Detroit steel gleamed on every corner and a new car was something families truly celebrated.

Goddard Motors was a wonderland of chrome and color. The lot stretched wide and bright, filled with rows of freshly waxed cars—Plymouth Furys and the sleek new Satellite Sebring Plus models. I still remember stepping through the showroom doors and being hit by that unmistakable new-car smell—a mix of vinyl, polish, and possibility. It was as intoxicating to me as any perfume could be.

My dad was the assistant leasing manager, a title that seemed impossibly important to my young ears. Leasing was still a new concept in those days, and I remember him explaining it to customers with patience and pride. To me, though, it wasn’t about business—it was about belonging. On Saturdays, I was at Goddard Motors, sponge in hand, helping wash the rental cars.

Those mornings were pure joy. The hum of hoses, the slap of chamois cloths, and the sight of sunlight glinting off a freshly washed hood felt like a ritual. Sometimes my dad would toss me the keys and let me move a car across the lot—an enormous thrill for a kid about to get his driver’s license. I can still picture the Cordoba with its fine Corinthian leather, its rich interior glowing like a living room on wheels.

And then there were the men who worked there—Rich, Skip, Norm, and Bill—each with their own sense of humor and stories to tell. They treated me like one of the gang, teasing me good-naturedly, teaching me how to dry a fender properly or check for streaks on a windshield. For a shy kid, that sense of inclusion meant everything.

But the car business, like the country itself, began to change. The Arab Oil Embargo hit in the early 1970s, and suddenly gas lines, mileage concerns, and shifting consumer tastes reshaped everything. The big, powerful Chryslers gave way to smaller imports. Goddard Motors eventually moved, then was bought out, fading from the map like so many neighborhood landmarks of that era.

My dad left the dealership long before that, trading the uncertainty of car sales for the stability of county government work. Still, I know those years at Goddard shaped both of us. They gave him pride in his craft—and gave me an early love for the smell of a showroom, the feel of a steering wheel, and the camaraderie of a good team.

Sometimes I think those Saturdays at Goddard Motors taught me more than I ever realized back then. I wasn’t just washing cars or tagging along with my dad—I was learning about pride in your work, loyalty among friends, and the quiet satisfaction of doing something well. When I look back now, I can still see him standing on that lot, a row of shiny Chryslers behind him and a smile that said he was right where he belonged. And maybe, in a small way, so was I.

Postscript:

All these years later, every time I catch that unmistakable new-car smell, I’m reminded of him—and of those early lessons that never really left me.