My first real date was with a girl named Cara. No last names. I’m not even sure where she is these days, which feels appropriate, because eighth grade was full of people who entered your life briefly and then quietly disappeared.

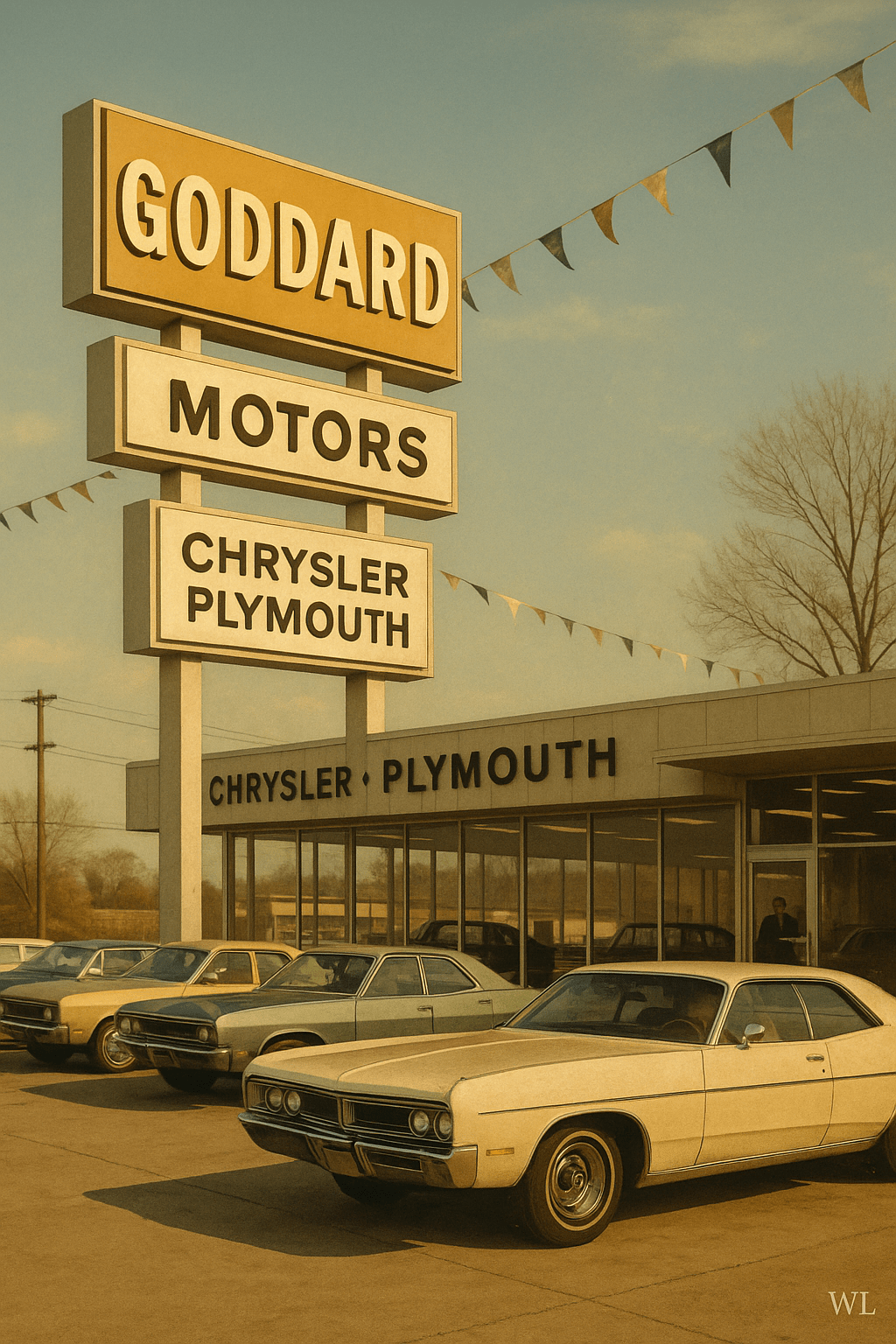

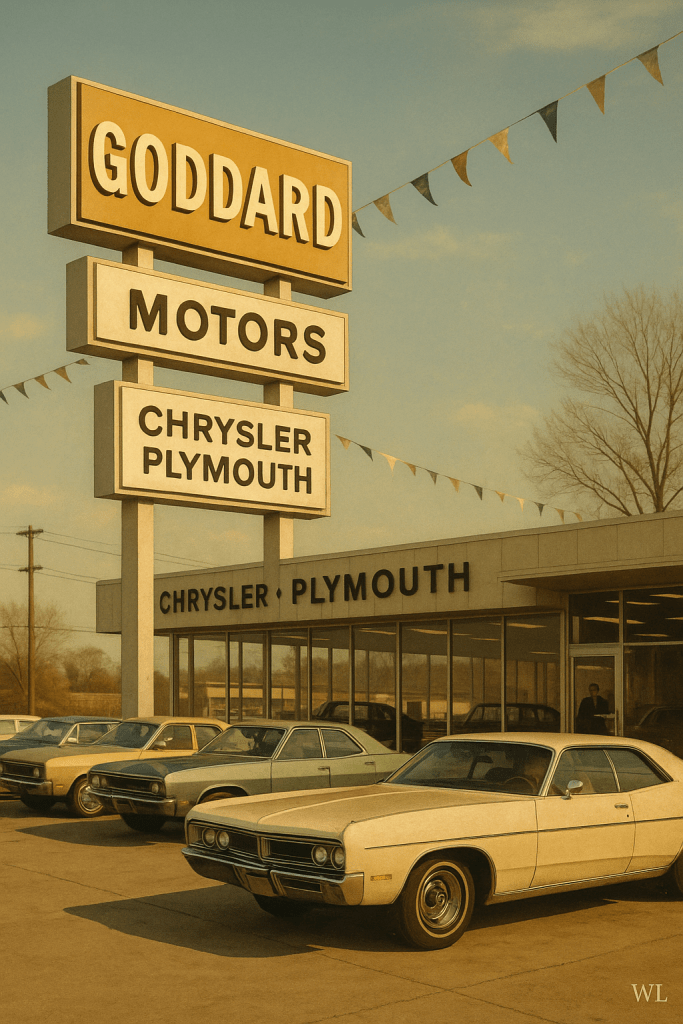

I took her to the eighth-grade social. She lived right up the street, just five houses away, which meant the ride home in my dad’s Cordoba was going to be long enough to matter but short enough to avoid any truly dangerous romantic expectations. We had known each other for a while, so asking her felt natural—less like a grand gesture and more like a mutual shrug toward something new.

The dance was held in the gym at Washington Junior High. The same gym where we ran laps and endured dodgeball was suddenly dressed up with crepe paper and dim lighting. There were snacks laid out in the kitchen, which felt incredibly sophisticated at the time. Romance, or at least the junior-high version of it, hung in the air.

I should admit right now that I was naïve and very much not a ladies’ man. I owned exactly one move, and it involved standing still while swaying slightly. Still, there was slow dancing. Careful, awkward, hands-placed-where-they-were-clearly-approved slow dancing. Maybe we almost cuddled. We weren’t as advanced as some of our classmates, who seemed to have learned these things from a secret manual the rest of us never received. But it felt nice. And at thirteen, nice was plenty.

When the evening ended, we headed home—five houses apart,bringing us closer to our respective front doors and farther from the gym floor. The next day, everything returned to normal. No declarations, no awkwardness, just school and life continuing on as if nothing monumental had happened.

Except, of course, something had.

Cara and I kept crossing paths. We went through four years of high school together and then a couple of years of college. Somewhere along the way, we developed a close and somewhat unique friendship. It was Cara who decided that if we were going to be business majors, we really needed to learn how to drink martinis, even though neither of us actually liked them yet. And it was Cara who almost convinced me to go skinny-dipping in her apartment pool at two in the morning.

Almost.

I was still cautious, even when pretending not to be.

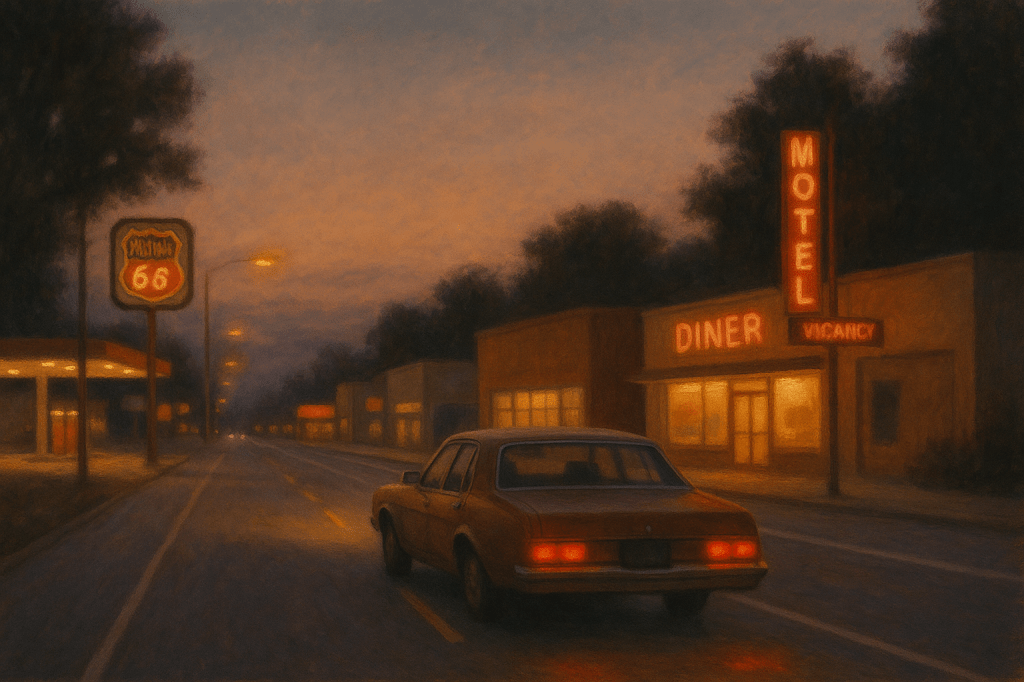

Eventually, life did what it always does. We drifted. Time passed. Careers, moves, and responsibilities filled in the space between memories. But every once in a while, without warning, I’m back in that gym—slow dancing, swaying awkwardly, doing my best with what little confidence I had.

I lost track of Cara years ago. But I never lost track of what that night taught me: that first dates don’t have to be impressive to be important, and sometimes the smallest moments—five houses, one dance, a night that ended too soon—stay with you the longest.